Do you recall when you were a kid and you experienced for the first time an unnatural event where some other kid “stole” your name and their parents were now calling their child by your name, causing much confusion for all on the playground? And how this all made things even more complicated – or at least unnecessarily complex when you and that kid shared a classroom and teacher, or street, or coach and team, and just perhaps that kid even had the same surname as you, amplifying the issue! What you were experiencing was a naming collision (in meatspace).

Simply because two different families (administrative entities), in different households (unique name spaces), selected the name du jour and forever labeled their offspring accordingly, you now have to suffer. It didn’t occur to them at the time (or perhaps it did) that it may well be the most popular name of the day and ripe for collisions throughout your life, or it may have been the least desirable name, or perhaps because of uniqueness or spelling, or because of known or yet unrealized historical artifacts, or perhaps it simply possesses some other attribute that only later in life would make it problematic or even more endearing.

Naming collisions happen all the time. When uniqueness within a name space is preserved, for example within a household among siblings, or jersey numbers on a ball team, it’s not a problem. But when you begin to merge name spaces or not preserve uniqueness, e.g., multiple households have like-named kids that attend a communal school, or father and son share the same given name, collisions may occur and it can be really problematic if not handled accordingly. In order to regain uniqueness you typically add prefixes to the names (e.g,. Big John Smith and Lil’ John Smith and Mrs. John Smith), or append suffixes (e.g., John Smith, Sr. and John Smith, Jr.), these new labels serve as discriminators in the namespace.

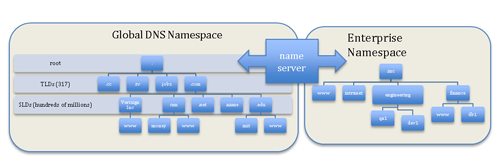

Enter the internet, a new kind of space, AKA cyberspace, a global network of loosely interconnected networks where billions of users and devices coexist. Absent some mechanism to preserve uniqueness of names across the space one might want to transact with [Big] John Smith and find themselves talking to his son or wife instead. As discussed in a previous post, for the global internet name space, uniqueness of names is ensured by the Domain Name System (DNS). The DNS employs a hierarchical allocation structure (think of an upside down tree from the root to the leaves) to enable safe predictable navigation on the Internet. These names are then used by applications of all sorts to transact: for example, big.john.smith.com would be a different identifier in john.smith.com namespace (household) than lil.john.smith.com.

In cyberspace, as in meatspace, names are used to identify an entity (e.g., a web or database server). However, because on the internet the DNS provides a global system for uniqueness of names, many folks naturally and immediately begin to make assumptions about the rigidity of those names and the spaces in which they exist – assumptions regarding both what does exist in that namespace and what is non-existent in that namespace. For example, assume you were building an internal network at an enterprise that you never intend to expose ‘directly’(ß operative word) to the internet and you have to develop a naming scheme for servers and desktop systems. To make this work and preserve uniqueness across the enterprise, you select an internal domain – let’s say .inc – as your base domain. Just to be safe, and because you’re clever, you check the current list of country code and generic top level domains (e.g., the 317 TLDs such as .com, .net, .cn, .me, etc..) and ensure there are no collisions with your internal top level domain in the global DNS, an important step if you intend to allow internet access from portions of the internal network. From there, you use team responsibilities to create subdomains (e.g., QA, DEV, SALES, FINANCE, HR, ETC..) in the .inc domain, and hostnames are based on some concoction of employee names and location (e.g., you-thisblog.engineering.inc), or some such schema.

Next, you need to support the ability to communicate securely with software engineering servers, finance databases and human resource systems and to be able to validate that when you’re connecting to a system (e.g., a code repository) it’s actually that system and not some imposter. To do this, you use the state of the art, digital certificates and public key cryptography – which mostly means you fire up a web browser and go buy some certificates (or acquire a managed PKI service) from one of any number of Certification Authorities (CAs). This then allows you to deploy digital certificates that can be used to authenticate the identity of your systems (e.g., you-thisblog.engineering.inc) and to secure communications across the network. Remember, you want to be sure that when your employees use their standard web browsers and email clients (FireFox, IE, Chrome, Outlook, etc.) that the security checks all pass muster.

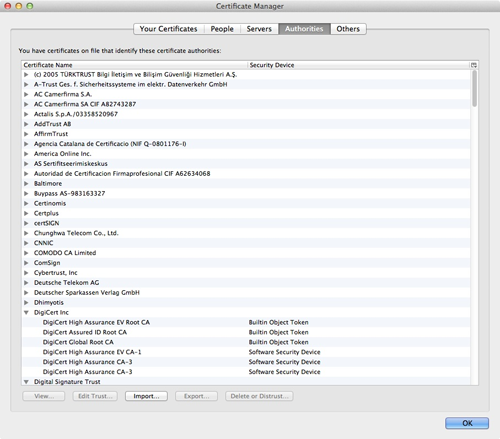

The only requirement you really have in order to make sure your users don’t get browser warnings, or connection failures, is that the CA you get the certificates from is embedded as “trusted root CA” (Authorities) in the applications you use – and that’s because this root CA is required for your browser to have a trusted way to bootstrap validation and ensure that when connecting to a server the certificate hasn’t been tampered with). Basically, when we use any “Relying Party’’ software (software that relies on claims for security-related tasks – e.g., like web browsers), we implicitly expect the software maintainers to keep our list of CAs fresh, current, and up to date. This is the heart of today’s state of the art public key cryptography, for end users. See Figure 1 from my Firefox browser Certificate Manager and Authorities tab (and see the Mozilla project Root CA store for more information on CAs embedded there).

Another example relates to a slightly different naming collision issue. In mid-March ICANN’s Security and Stability Advisory Committee published an advisory titled SAC057: SSAC Advisory on Internal Name Certificates. The crux of the problem is this: if anyone can go get a certificate issued that allows them to attest to the identity of systems within some previously unused namespace, and then that namespace finds its way into the global DNS namespace (e.g., .inc is delegated in the root), those same techniques and certificates can (will) be employed by miscreants to compromise otherwise secure communications related to that namespace. In fairness to the CAs, these certificates were only supposed to be used internally by the recipients (users typically have to agree to that when they are issued) such as .inc and really should NOT be visible on the global Internet facing services, although some do tend to leak out, as discussed in SAC057 and in the EFF SSL Observatory.

ICANN did take a stab at addressing this issue after SSAC brought it to their attention. Specifically, they worked with the CA/Browser (CAB) Forum on efforts that led to the development of Ballot 96, which in a nutshell says that participating CAs should stop issuing certificates that end in an applied-for-gTLD string within 30 days of ICANN signing the contract with the registry operator, and they should also revoke any existing certificates related to that applied-for-string within 120 days of ICANN signing the contract with the registry operator. While this is great progress, there’s still much work that remains to mitigate this vulnerability, to include recognition that:

- Not all CAs are members of the CA/Browser Forum (many are not)

- Certificate revocation is largely ineffective on the internet for many reasons

- 120 days is not a practical amount of time for an enterprise that has been using some namespace for years to reconfigure their infrastructure, obtain and deploy new certificates for all their systems, etc. So, when CAs begin to try and effectuate this, the timelines will surely expand as they can’t be expected to do things that would disrupt their customer networks only months after selling them updated certificates within that very same namespace

- Astute attackers would disable revocation checks (e.g., block status queries) when launching man in the middle (MITM) attacks.

While I commend ICANN for some notable progress in this area in a number of weeks after SAC057 was brought to their attention, the vulnerability is far from resolved. And whether or not .inc or any other namespace should have been used by naïve users on the internet in the first place, many of those decisions were made in good faith and based on best current practices, and have been operational for years. Delegating strings that could impact operational networks without some attempt to thoroughly and accurately evaluate the risks of those delegations and the impact on users connectivity or consumer security IS unilaterally transferring risks to consumers (e.g., the Internal Name Certificate issue), their networks and applications can break when these delegations occur, and we ought not be doing that absent some careful consideration of the implications.